Ultima Ratio Regis – Designer’s notes

Ultima Ratio Regis is born from the desire to design a game capable of covering the modern age (as does the well-known “Europa Universalis”) with modern, fluid and manageable mechanics, and correcting many bugs that over the past 20 years we have seen in many historical “multiplayer” games. We know that many fans are aware of these flaws, and some have already asked us how uRR deals with them. We are trying to clear up some of these doubts.

Powers in play

One of the aspects that may draw more attention to those approaching the game for the first time is that each player controls several powers. There are few games where this happens and most share the same flaw: players end up using all their countries in a coordinated way, as if they were just one, which is not historic at all.

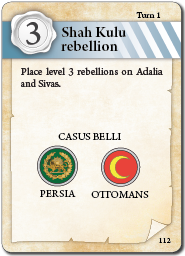

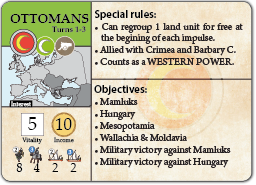

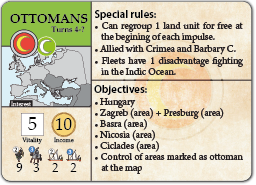

In Ultima Ratio Regis the powers function as sealed compartments, and they do so with mechanisms and rules that are totally credible. To begin with, the map is divided into large theatres of operations and each power has “interest” and can operate in only a few of them (in the rest of theatres it can hardly do anything). Each power also has very specific objectives, war events and “casus belli” that lead it in the historical direction. Let’s say a player controls France and Persia; the game doesn’t prevent him from declaring war with both at once on the Ottoman Empire, but doing so with France simply doesn’t make sense. France will suffer a significant penalty for not having casus belli; it will barely be able to conduct military operations against the Ottomans because it has no interest in the Eastern Mediterranean theatre of operations. And all this in order not to obtain a single victory point.

On the other hand, controlling several powers has many advantages for a game of this kind: You don’t need “filling rules” or “accounting” with the country’s economy so that players have something to do when they’re not at war (in uRR you’re always involved in wars, sometimes several at the same time, it’s normal that you’re overwhelmed). Players are more involved in everything that happens in the game, as they operate in different theatres all over the map and play countries with very different styles of play at the same time. With uRR mechanisms it is easy to add new powers or make them disappear, and it can accommodate a very variable number of players. All powers are governed by the same general rules and less special rules are necessary.

All this does not mean that the player can’t have a power that is his favourite or main power, either because of personal preferences or because it is really the most important historically speaking, or the most active.

Map and counters

You may have been frightened to see how many counters the game has (more than 700). Don’t worry, the reason for so many counters is mainly that there are many countries. In practice, on the map there are relatively few, even great powers like Spain or the Ottoman Empire barely have a dozen military units on the board, and they also have them stacked forming a few armies or fleets.

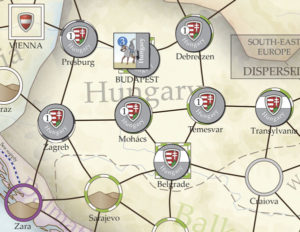

As for the control markers, most areas on the map are already the color of the power that normally controls them, so very few are placed, and the map is usually quite clear. This is so to extremes that require some explanation, as is the case of Hungary and the Mamluks. If you look at the map you will see that, unlike the other powers, these two do not have the map areas of their color, but are the color of the Ottoman Empire. The reason is that these countries usually last only the first two or three turns, then collapse, disappear, and their areas almost always end up in the hands of the Ottomans. If their color had been used on the map, this would have saved you from placing control markers of those powers for the first 3 turns, but would force you to use Ottoman markers for the remaining 17 turns, it is much cleaner and more practical the opposite. This does not prevent Hungary from ending up in the hands of Austria (though that happens infrequently), or Egypt in the hands of a slightly daring (and reckless) Venetian player.

With the Spanish colonial empire something similar happens, most of the areas of South America and Central America are already the color of Spain, when at the beginning of the game (1490) Spain has not even discovered America, it happens that in a matter of 5 or 6 turns almost all those areas end up in their power and continue like that until the end of the game. Again it is more practical to use the color of Spain on the map, cover them during the deployment with control markers of active independents, and as Spain conquers its empire, instead of placing its control markers, it removes the independents, leaving the map cleaner and cleaner. Something similar has also been done with Siberia and certain parts of Russia such as the Golden Horde, Astrakhan or Livonia.

Evolution of powers

All the information related to a power (vitality, economy, special rules, objectives…) is condensed in a card that can change with time. As the game progresses, some powers, such as Spain or the Ottoman Empire, will see how in certain turns their card is replaced by a worse one, with less vitality, less income, less elite units,… On the other hand, other powers, such as England, France or Russia, will see their natal card improve and their abilities increase, going from being second order countries to superpowers.

There are powers that are subject to collapse rules and may disappear after losing a war (such as the Mamluks or Hungary), or that will end up becoming minor states no longer controlled by any player (Denmark or Venice). Others join as the game unfolds (such as Sweden and Holland), or will only last for the duration of a war (such as the Huguenots and the Catholic League during the French Wars of Religion).

Elements of decision

After reading the three previous sections you may be wondering if uRR isn’t a game that’s too rigid and historically tracked; the answer to that question is yes and no at the same time. It’s a game that pretty much follows the historical course, but allows for a lot of variation within it. Following the example of a player who controls France and Persia, we have that during the first game turns, France is continuously at war with Spain (Italian Wars), and Persia half the time is at war with the Ottoman Empire. It is a historical script that is always the same, however this is only a framework within which many things can happen. Some turns of the Italian Wars will be marked by big field battles with many casualties for both sides, other turns players will do almost nothing and will be busy on other “fronts”; and others can be a complex maneuvering war with hardly any battles. In addition, in some turns other powers such as Venice or Austria may (or may not) intervene.

To illustrate the above, if on a turn France suffers a catastrophic defeat in Italy, the player will probably turn over the resources of his cards in an intense campaign in Mesopotamia with Persia. In another turn or game, Persia may do almost nothing and most of the player’s resources will be absorbed by France and the Italian Wars. Multiply this by the number of powers in play (which may be 15 or 16) and add to the cocktail unexpected side changes from key minor powers (e.g. Scotland in the middle of a war between France and England), technological advancements, or casus belli and wars outside the historical script (which there are also), and the result is that no two games are the same.

Generic Events

In uRR there are two types of events; historical events (which take place in specific turns) and generic events. Each turn you have to assemble the deck of cards and this is done by taking all the historical cards from that precise turn, and then a random selection of generic cards that complete the deck up to about 40, which are then dealt to the players.

The latter may appear to be a filler, but they are not. Within these generic cards are the activation of minor powers (which allow them to change their ally), unexpected casus belli, or technological advances that can alter the course of a war. The introduction of only a part of these events and also at random, adds tension to the game and makes unpredictable how it will unfold that turn.

Combat System

Perhaps because of its appearance (graph map, card driven game, and very generic troops) uRR seems like a purely strategic game, where the main decisions players can make regarding their armies or fleets are reduced to making battles. It is actually an almost operational game. This is thanks to the combination of concepts such as battle size, disadvantages and finally subjugation combat.

The size of the battle can vary according to terrain, type of general or naval superiority. This is meshed with a system of disadvantages that can reduce the quality of troops, also depending on terrain, generals, naval support, etc. These are some of the factors that determine when and where players are interested in fighting. Sieges and subjugation combat complement the above system, allowing powers to force their enemies to spend far more resources to advance and occupy areas. This type of strategy causes attrition to the enemy in the form of disbanded units, allowing players to fight a war almost without making battles. The duration or cost of a campaign and how long a player can use this delaying tactic will also depend on how far he can yield ground without beginning to lose key areas or allies. Or simply whether he is interested in making the campaign shorter or longer for other strategic considerations.

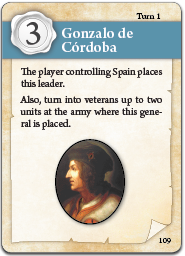

Leaders

The random selection of generals is another element that serves to add decision elements to the game. Since striving for a general of a particular type can be very costly or simply not getting out, players often end up adapting their strategy to what they get. In this way, a tactical general can encourage the player to look for decisive frontal battles, while a determined general can push him into a campaign of attrition; or an admiral open up the possibility of attacking enemy targets through complex naval operations and landings.

Historical generals (which enter the game by event) in earlier versions of the game differed from generics in that they could have more than one ability or characteristic. This gave rise to complex situations to resolve and finally we changed it; now they also have a single ability.

These historical generals still have the advantage that you don’t have to pay unrest for them, the player knows beforehand when they are going to appear, and also what kind they are going to be. In addition, when some of them enter into the game “convert” units into veterans (the event card itself indicates this), these veterans represent the reforms in the army that introduced these exceptional characters; something that has happened since the time of Philip of Macedon. This standardizes and simplifies how generals work, but at the same time the historical ones are better represented. The loss at the end of the turn of half of the veterans represents in this case that other powers end up copying those reforms (applying again for it a generic rule that affects equally the veterans resulting from combat).

Unrest

What in uRR we call unrest integrates not only the discontent and level of internal turmoil of a power, but also the state of its economy. In the early versions of the game economy and unrest were separated, but they were two elements with many communicating vessels. At one point, we realized that it was more practical and simple to integrate everything into a single system.

A high level of unrest may represent that the power is heavily indebted, which in the end translates into internal turmoil (excessive taxes, inflation and difficulties in the daily lives of the inhabitants of that country). It can also be interpreted in reverse; social unrest for whatever causes (political, religious…) ends up translating into economic difficulties, that is, less capacity to collect taxes or to recruit and maintain the army.

Vitality of the powers

Vitality is one of the most representative characteristics of the strength of a power, and it is intertwined with many other mechanisms of the game, in a way that is difficult to see just by reading the rules.

For example, during a war a power has as many morale points as it has vitality. If at any time it runs out of morale points it must surrender immediately; this often conditions the way a military campaign is waged: Powers with very few morale points, such as Hungary, which has only 2, are fragile and often risk everything in a single battle as was historically the case (defeated in a field battle over a key area, they suddenly lose 2 morale points and must surrender). However, powers with many morale points (4 or 5) not only have more resistance during a war, but they can play an attrition campaign against powers that have fewer points, knowing that in a long war, their opponent will be forced to surrender sooner.

When betting for smaller allied states or technologies, powers can bid at most as many points of unrest as their vitality, so those with more vitality also have a better chance of getting these allies and technologies.

Vitality also influences commercial competition, giving a certain advantage to powers with a higher level.

Finally, power’s unrest is compared at the end of the turn with its vitality, and depending on whether it is lower, higher, or more than double the vitality, it may suffer different penalties.

Morale and development of wars

Another original aspect of uRR is morale during war. As noted above, a power has as many morale points as vitality points, represented by counters. Each time a power loses a battle, an ally, or a key area, it must surrender one of its morale counters to the one who inflicted the defeat. If it ever run out of morale points, it surrenders immediately.

When one war is over, the winning power is the one that took the most morale points from the other, and the war reparations the winner can demand are as many as the difference in morale points. In uRR the enemy territories occupied during a war are not automatically ceded to the conqueror; he has to demand them by spending war reparation points, and those that he cannot (or does not want to) demand, must be returned to their original owner (this concept will sure be familiar to those of you who know the computer game Europa Universalis).

In addition, lost morale points can be translated into points of unrest at the end of the war (war fatigue), so it is not the same a war where the winner has 2 morale points of the loser and the loser 0 of the winner, than one where the points are 5 and 3 respectively. Although the war reparations are the same (two in both cases), in the second case the war has been more intense and harder, and the impact on unrest (or economy) will be more negative.

This agile and simple system avoids the “total wars until the last man” that are antihistoric and distort many other games of this style.

Diplomacy

Diplomacy without any limitation can be fun in lighter games, but it does not take into account the historical conditions of the time and in our opinion, it is neither credible nor realistic.

In uRR wars are conditioned by historical events or casus belli as seen. One power can declare war on another without having casus belli, but when it does it has to give this last one morale point, that is, it begins “losing”. This, in addition to being a necessary penalty for the game to be historical, represents the internal opposition to a war that has no reason to be declared. Despite this, these declarations of war happen on some occasions, but the player has to know very well what he is doing. Doing so with a power that has 5 morale points (like the Ottoman Empire) against one that has only 2 points (like the Mamluks) can end up succeeding, but against a power with 4 morale points (like Austria for example) it is very dangerous.

Alliances between powers are also limited to historical ones, and cooperation between allies is limited, broadly speaking, to sending expeditionary corps, strategic redeployments, and naval support.

Likewise, there is quite a bit of diplomacy between players, although it is somewhat different from other games of the style. It’s usually a one-on-one diplomacy, which revolves around what a player’s intentions are regarding one of his powers; how far he’s willing to continue a war or how the support of a possible ally is going to materialize, to give a few examples.

It’s also not uncommon to see the same two players carrying enemy powers that are bleeding to death in the East, for example, while happily collaborating with two other powers, allied in the West.

Economy

This is another aspect that can end up deforming such a long game if it deviates too much from history. It has been tackled by assigning each power a fixed income that is indicated in their natal card. It is possible to earn additional income by trade or by controlling key non-home areas.

In general, for most powers the fixed income constitutes the bulk or even all of their resources, although there are some such as Spain, Venice, Holland or the Ottoman Empire that can double them with their trade and conquests. This income is used to maintain military units.

On the other hand, a power can spend more than it earns, which will cause its unrest to increase at the end of the turn (which, as we have seen, also represents the indebtedness and progress of the economy). This will lead to reduce its activity in subsequent turns in order to recover its economy. This system allows the powers to stretch beyond their resources in critical moments, but at the same time prevents them from ending up permanently “out of the game”.

In addition, the system is quite round and simple: The incomes of the bulk of the powers range between 10 and 20 points; the maintenance of many units costs 1 point (fleets 2) so that calculating the economy of all your powers and the consequences of their levels of unrest will only take you 2 or 3 minutes each turn, and you can do this without taking notes or using counters.

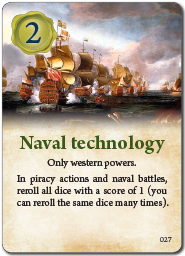

Technological advancement

It is introduced through four generic event cards that give an advantage to the powers that get them but only until the end of the turn. This represents it’s copied by all powers after a few years.

The system is complemented by some additional advantages that may last longer and affect only some powers (such as the Spanish “Tercios”). Also with events that can create permanent changes in the game from certain turns onwards (such as the nautical Astrolabe, which increases the distance of naval operations).

Narrative

These days, a large number of games are published, and it is common to hear about mechanics, but less about narrative. The reason is surely that many of these novelties are “eurogames”, so abstracts that their subject can often be replaced by another one that alters little more than the graphic aspect. This is not the case for most historical games and wargames. Those of you who are fans of these games and who, like us, have been playing titles from companies such as Avalon Hill or GMT Games for several decades, I’m sure you remember, years later, plays with extraordinary or surprising results (nobody remembers a game of Settlers of Catan ten years later).

In uRR the historical events that come in and out of the game in their corresponding turns are an essential element in the construction of that narrative. Most have a major impact on the game, although some you’ll see have very little effect, or even none as in the case of the “Luther” event. These cards could be eliminated, but we have deliberately included them: they serve to make the narrative more complete, and they also have a didactic function, showing the players what we think are the most significant events of the era.

Secondly, historical games and wargames would not be complete simulations without random elements. These basically represent everything that is impossible to cover with the rules because it is too extraordinary, exceptional or rare, but that we can often read in history books. Ultima Ratio Regis has three random elements:

- The random distribution of events between players, as in all card-driven games, serves to construct a story that is different in each game, but at the same time “rhymes” always with what happened historically.

- As for combat, if you’ve looked at the rules or examples, you’ve seen that roughly speaking it’s based on rolling a six-sided die for each participating unit, to get a result that can’t be less than the quality of the unit (when it is, it’s changed for that minimum result). This means that in the long term, the armies with the best units end up victorious most of the time, but at the same time allows armies of inferior quality to win exceptionally thanks to a good dice roll. Again this is a necessary element, as such things happened. In this way, at the same time it contributes to make the game narrative epic and unforgettable, making it possible, for example and against the odds, for the Mamluks to defeat the Ottoman Empire in a war, for the Spanish Armada to land the “Tercios” of Flanders in England, or for the Ottomans to conquer Malta.

- The last element that makes an important contribution to the narrative are the exceptional generals, of which we have already spoken, who arouse true feelings of pride and admiration, or disappointment and disenchantment.

Conclusion

In short, you have in your hands a game with quite a few original mechanisms, which is the culmination of almost two decades of talks and dissertations around all the historical “multiplayer” games that we have played.

You may initially find it hard to see its amplitude, but we trust that when you get to know it, you will begin to appreciate it, and above all, to enjoy it as we are doing.